The primary goal of a research paper is to convince its readers and scientific communities of the novelty and relevance of the study presented in the paper [1]. Scientific publications are targeted towards a certain community of readers, which is why scientific argumentation takes a predictable structure [2]. In this document, I describe two different models of the structure of scientific texts: rhetorical and argumentative. The nodes we describe here, for both argumentation and rhetorical models, are taken directly from the annotations of the Dr. Inventor corpus [3]. I am working on to find new relations that hold between rhetorical components.

Scientific Argumentation

In this section I will attempt to describe scientific texts in terms of argumentative components and relations. Argumentative components make the nodes of the argumentation graph and the relations make the arcs.

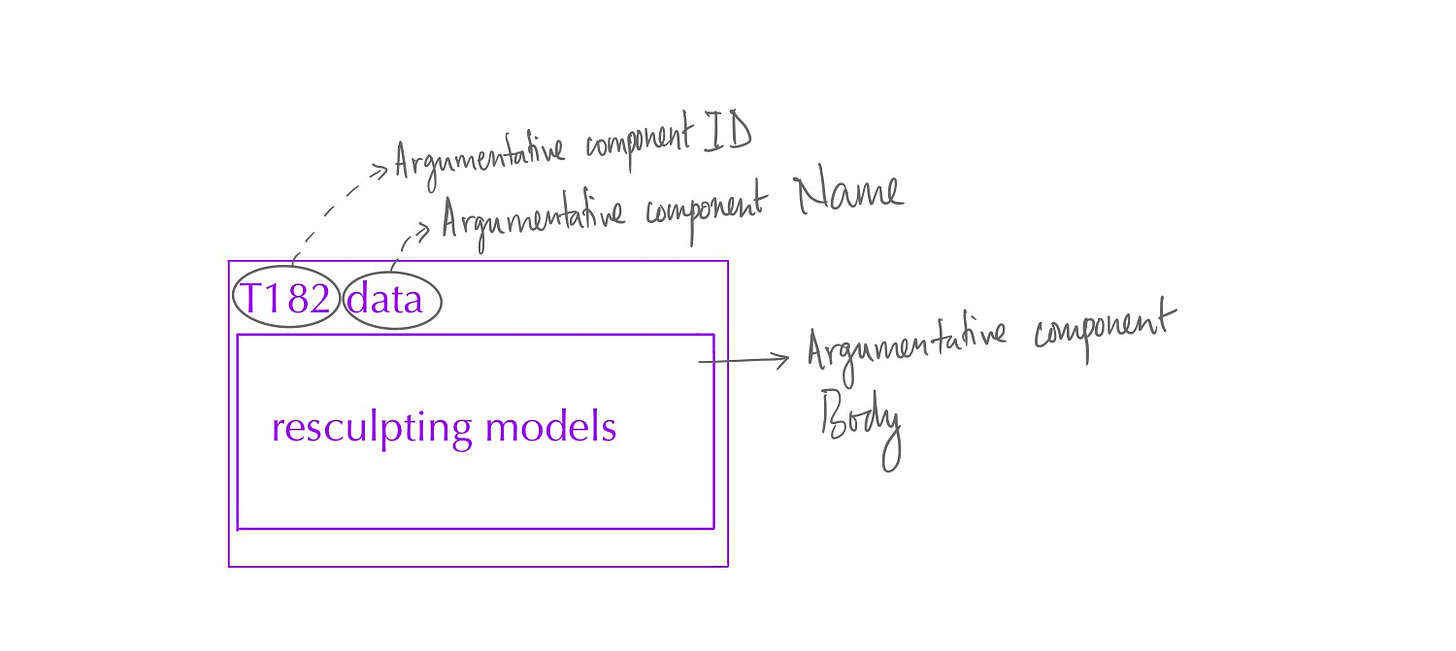

Argumentative Components

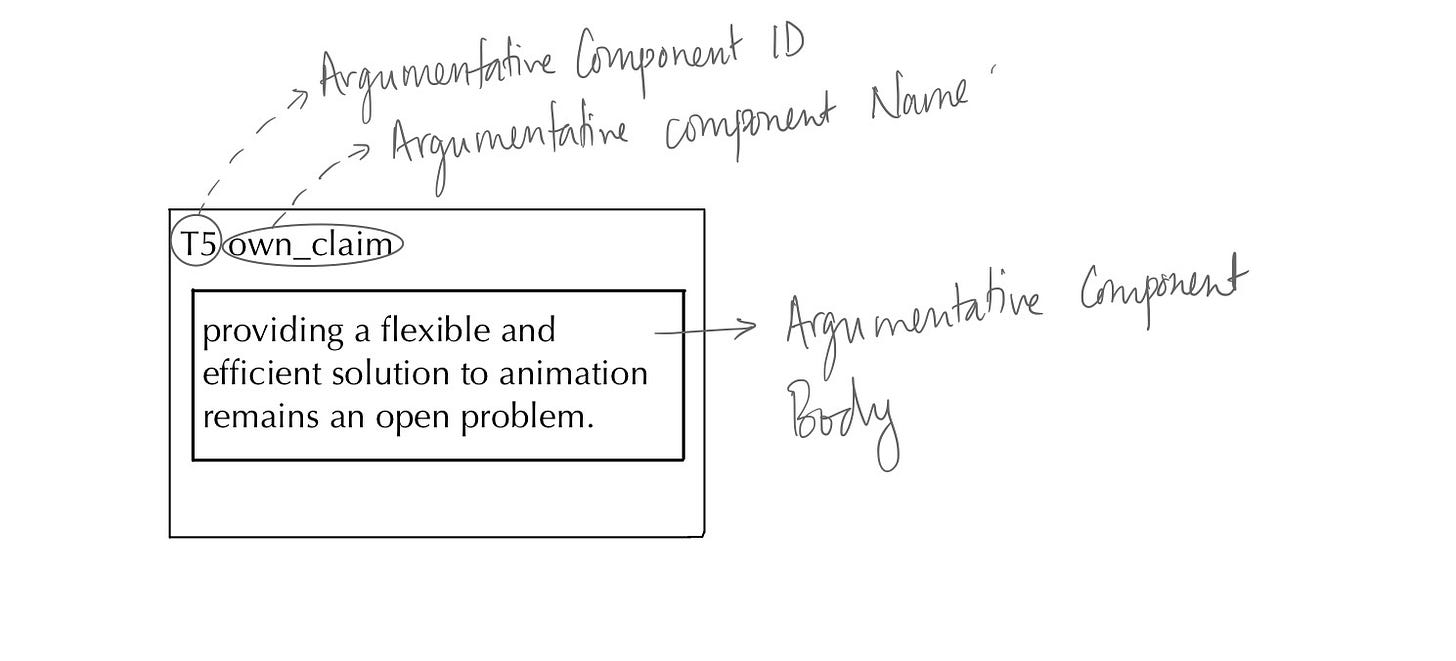

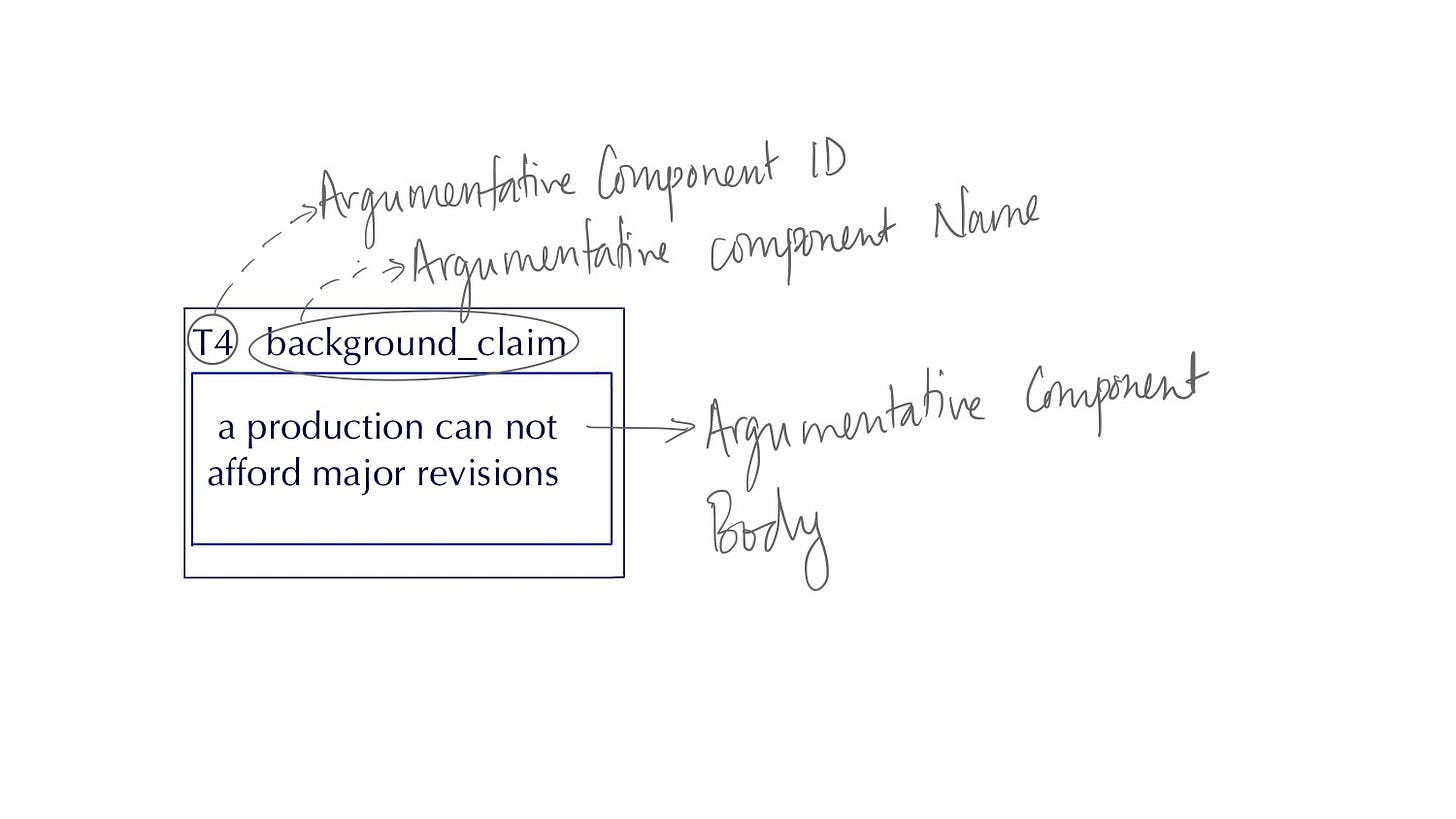

Dr. Inventor has been annotated for three argumentative components by [4]. The span of these argumentative components are not limited to sentence boundaries. They can be of any length and can span over multiple sentences. The three argumentative components are described below.

Own claims represent general argumentative statements or claims made by the author that closely relates to the author's own work.

Background claims are general claims that related to the background of author's work.

Data node represents facts and information that support or contest a claim.

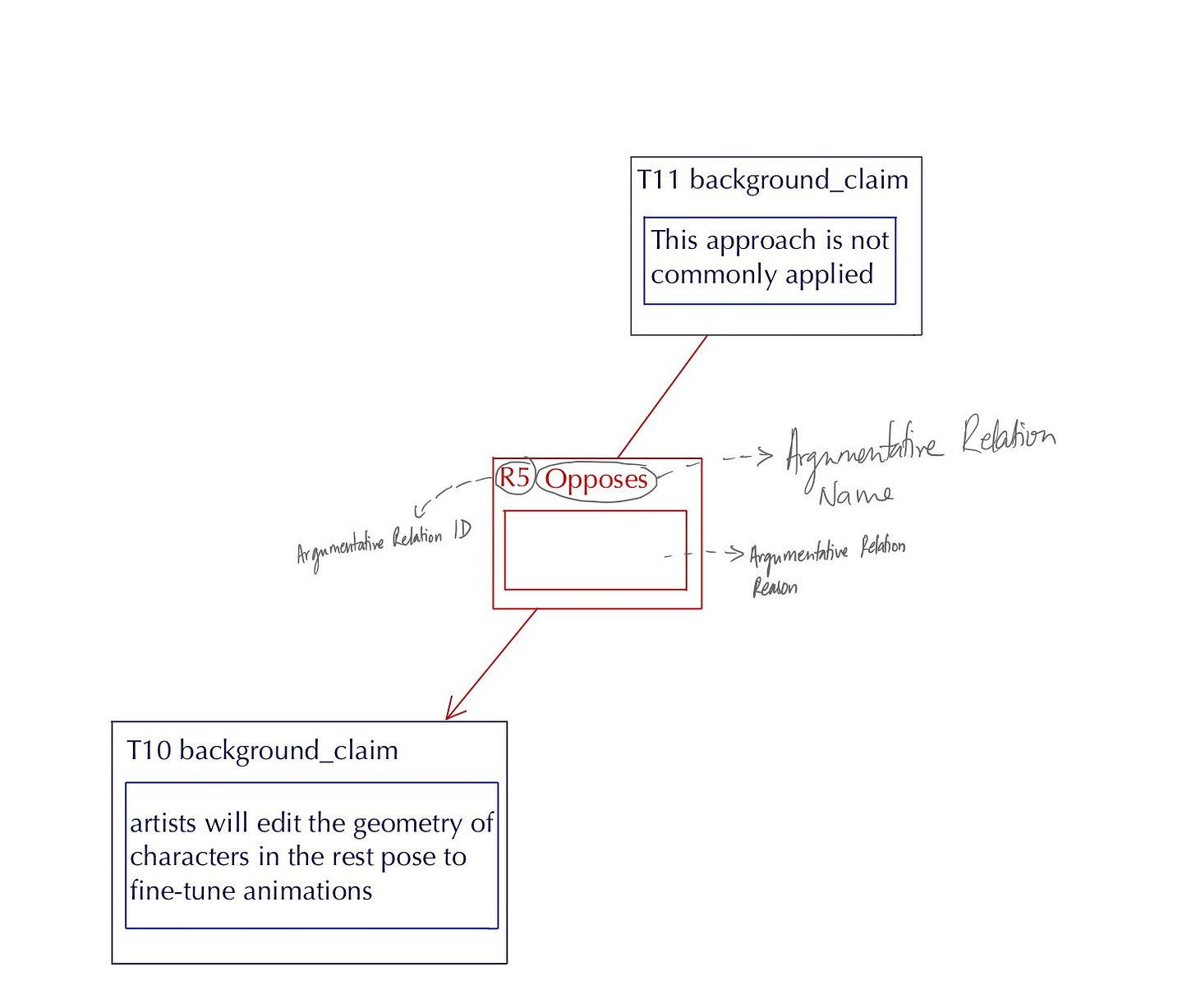

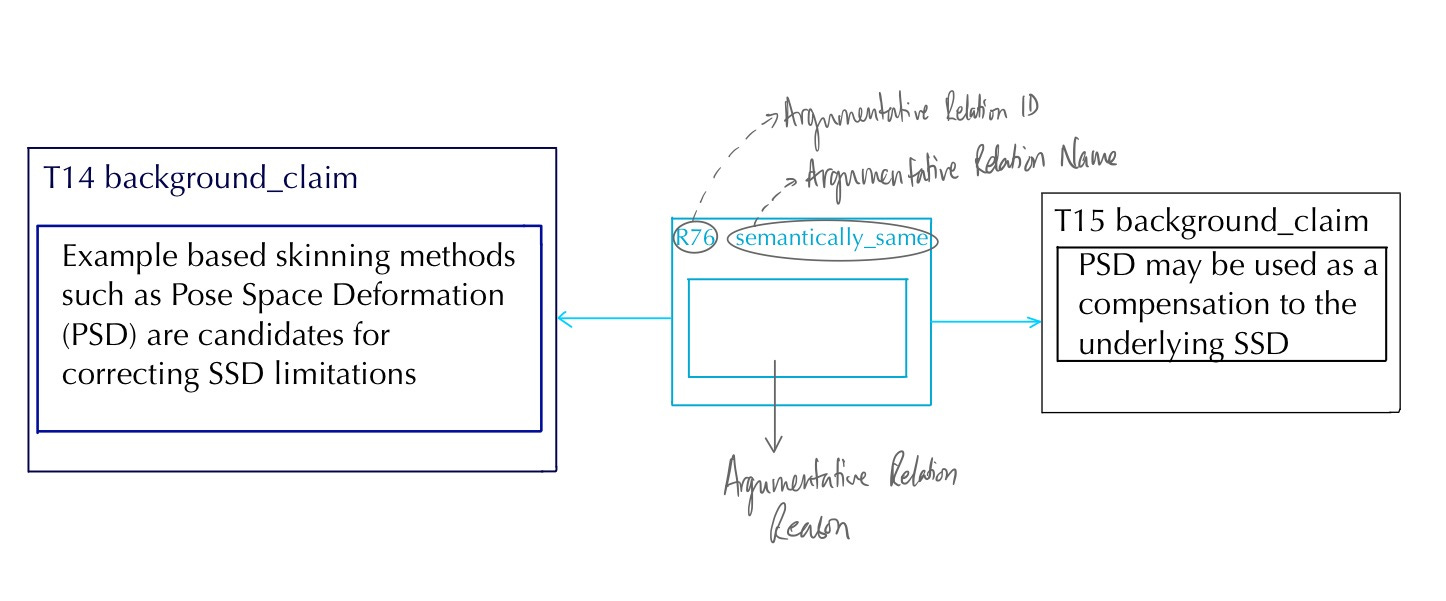

Argumentative Relations

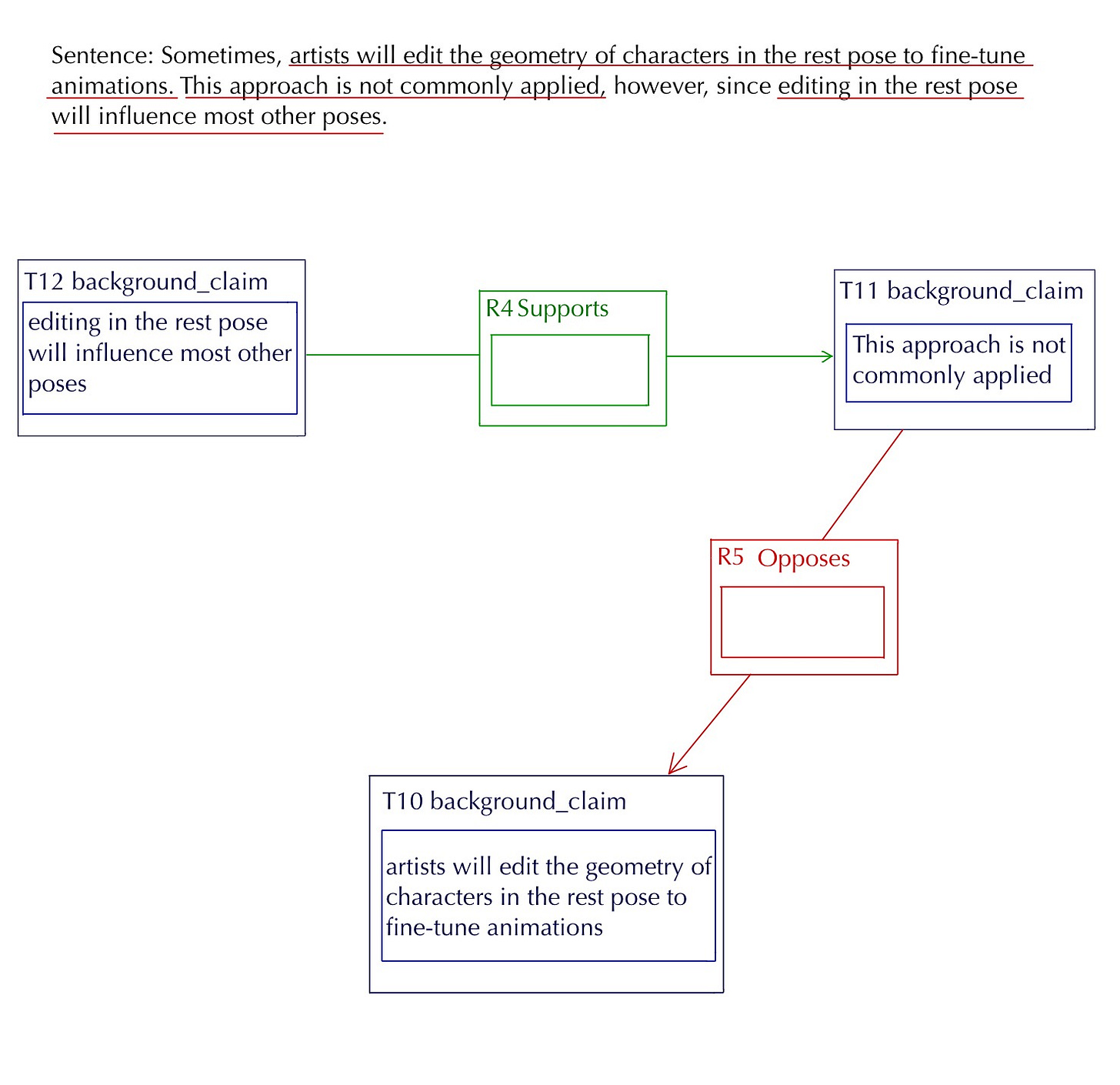

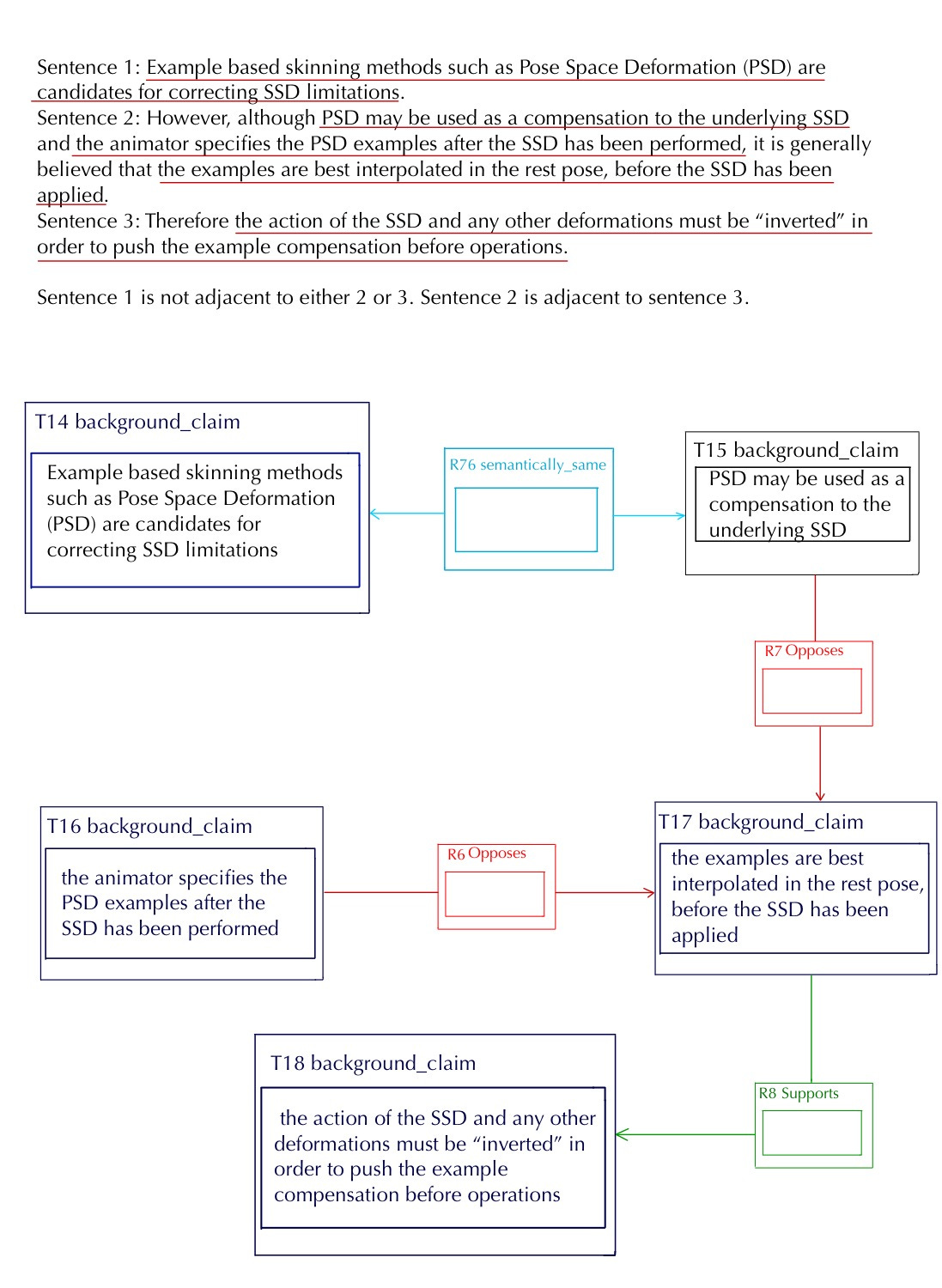

In the corpus, argumentative relations are composed of two argumentative text units Arg1 and Arg2. For our ontology, we plan to introduce a text field for each of the relation arc that contains reasons of the relation. Three argumentative relations type have been defined. They are:

Support relations hold between two argument components, Arg1 and Arg2. Arg1 supports Agr2 means Arg1 strengthens the claim being made in Arg2.

Oppose relations, like support, hold between two argument components, Arg1 and Arg2. However, Arg1 opposes Agr2 means Arg1 weakens the claim being made in Arg2.

Sematically same relations hold between two argument components, Arg1 and Arg2 that are two occurrences of the same claim or data.

Rhetorical View of Science

Scientific publications are designed to persuade. Persuading a reader of the value and novelty of research being described in a scientific publication requires the author to make different rhetorical moves. Rhetorical view of science views scientific texts as rhetorical objects/components with with a specific rhetorical move. These rhetorical components are described in this section.

Rhetorical Components

Rhetorical components are sentences that serve different rhetorical roles in writings. Sentences in Dr. Inventor has been annotated for rhetorical roles. The span of a rhetorical component is limited to sentence boundaries and no relation has been defined between these components. Based on the Dr. Inventor annotations we have the following eight different rhetorical components.

Background: Represents sentences that help to understand the overall problem that is being addressed in the publication. These include sentences that describe the commonly accepted knowledge and related work in the area of research.

Example: An early contribution concerning the animation of deformable objects is [Magnenat-Thalmann et al. 1988], which considers the movement of a human hand.

Approach: Sentences describe the models, frameworks, and experimental setup of investigation of the research discussed in the publication.

Example: Our basic idea is to change the interpolation domain: we interpolate transformations itself instead of transformed vertex positions.

Challenge: Describes the problem statement, current challenge, and gap in the area of research and motivation of the study.

Example: Although LBS is very fast and advantageous to graphics hardware, it suffers from inherent artifacts, known as ”collapsing joints”, ”twisting elbow problem” or a ”candy-wrapper artifact”.

Challenge_Hypothesis: Represents sentences that describe a current challenge and how it can possibly be addressed.

Example: We observe that we can help avoid the collapse problem by avoiding blending transformations that are so dissimilar.

Challenge_Goal: The sentences that describe the current challenge/gap that is being addressed in the publication.

Example: The paper discusses also theoretical properties of rotation interpolation, essential to spherical blend skinning.

Outcome: Includes sentences that describe the findings of the research.

Example: For small deformations, both algorithms produce similar results, as in the second row of Figure 6 (although a small loss of volume is noticeable even there).

Outcome_Contribution: Special outcome sentences that describe how the research contributes to the area of research.

Example: In contrast to other methods, the SBS does not need any additional information, such as the example skins.

Future Work: Describes the future research that can be done to improve the solution described in the publication.

Example: It would be interesting to find out how much can be the SBS results improved by a set of weights especially designed for SBS.

References

[1] Swales, J. M. (1990). Genre analysis: English in academic and research settings. Cambridge University Press.

[2] Kintsch, W., & van Dijk, T. A. (1978). Toward a model of text comprehension and production. Psychological review, 85(5), 363.

[3] Fisas, B., & Padró, L. (2016). Multi-level annotation of rhetorical entities, relations and structures in scientific articles. In Proceedings of the 10th Linguistic Annotation Workshop (pp. 102-111).

[4] Lauscher, A., & Glavaš, G. (2018). Argument Component Annotation: Towards Efficient Argument Analysis and Retrieval in Large Corpora. In Proceedings of the 2018 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP) (pp. 2558-2569).